Different Loyalties: A Tale of Fear and Loathing in Laos

Meritocracy was never a peaceful affair in the European empires.

Touby Ly Foung.

Tribal leaders were some of the most ardent supporters of the European overseas empires. One such individual was Touby Ly Foung (1919-1979), a Hmong of the Ly clan who was born in the French protectorate of Laos. He experienced the benefits of French imperialism as his father, Ly Xia Foung, was able to gain the trust of French officials. Touby’s loyalty was so deep for the French that he fought for them against Japanese militarists and Indochinese communists. However, this was not a universal sentiment among the Hmong community in Laos, as the trust placed in Touby’s clan in dealing with local administrative matters alienated some of his relatives in the Lo clan.

The origin of Touby’s family in Laos began when his paternal grandfather, Ly Dra Pao, migrated from Qing China in 1865. According to Touby, his grandfather had rejected assimilation into Han society by declining to marry the Chinese wife his adopted parents had selected for him.1 Instead, he returned to his native village to discover that his Ly clansmen were impoverished and stripped of their land.2 In the conversation that Dra Pao apparently had with his uncle, Touby writes:

“Dra Pao’s uncle said to him, “The country was in upheaval long before you were born. The Chinese mandarins forced heavy taxation upon us. The Ly clan, who had been administrators of this land, could not collect the demanded tax, so they had to sell their land to the Xiong clan. Then they migrated south. Those of us who remained had to gather our last dimes to pay off the Han administrators, becoming destitute in the process. Now we possessed only one paddy field each, just enough to keep us from starvation… Twelve years ago your uncle Tong Kia and I heard that the southern country was sparsely populated. The land is new and unclaimed. We also heard that Aunty Mee, who had married into the southern region, has had a good life. Ten years ago, after hearing this news, your uncle Tong Kia left for southern territories. I have not heard from him since. You are still young and vigorous. Go search for Aunty Mee and see how Uncle Tong Kia has been faring.”3

Dra Pao became a porter for a Chinese merchant and travelled to the district of Nong Het in Laos.4 The uninhabited hillsides around Nong Het were first settled by three Hmong clans - the Ly, Mua and Lo - as its rich soil was suitable for their slash-and-burn agriculture.5 Despite being a member of the Ly clan, Dra Pao was rejected by four aristocratic clansmen.6 Dra Pao not only had no relation with them, but he was not a native of Sichuan province where they originated nor was his association with a Chinese merchant viewed favourably by them, as their father had fought the Qing dynasty.7 This caused Dra Pao to establish his own village in Nong Het and marry two women respectively from the Thao and Yang clans.89 His marriage to the Thao woman produced Ly Xia Foung.

Wealthy Hmong men historically had multiple wives (polygyny) as it elevated their socioeconomic status.10 Dra Pao’s non-aristocratic background did not prevent him accumulating enough wealth to become a part of this set. However, Mai Na M. Lee stipulates that the rejection by the Ly aristocrats might have scarred Xia Foung and motivated him to prove his worth in his later life.11 Having become a well-educated man through his association with Chinese merchants in Nong Het, Xia Foung’s daughter Mao Song states that he caught the attention of the fourth wife of Lo Blia Yao, a pro-French Hmong leader.12 She persuaded Xia Foung to become her husband’s secretary.13

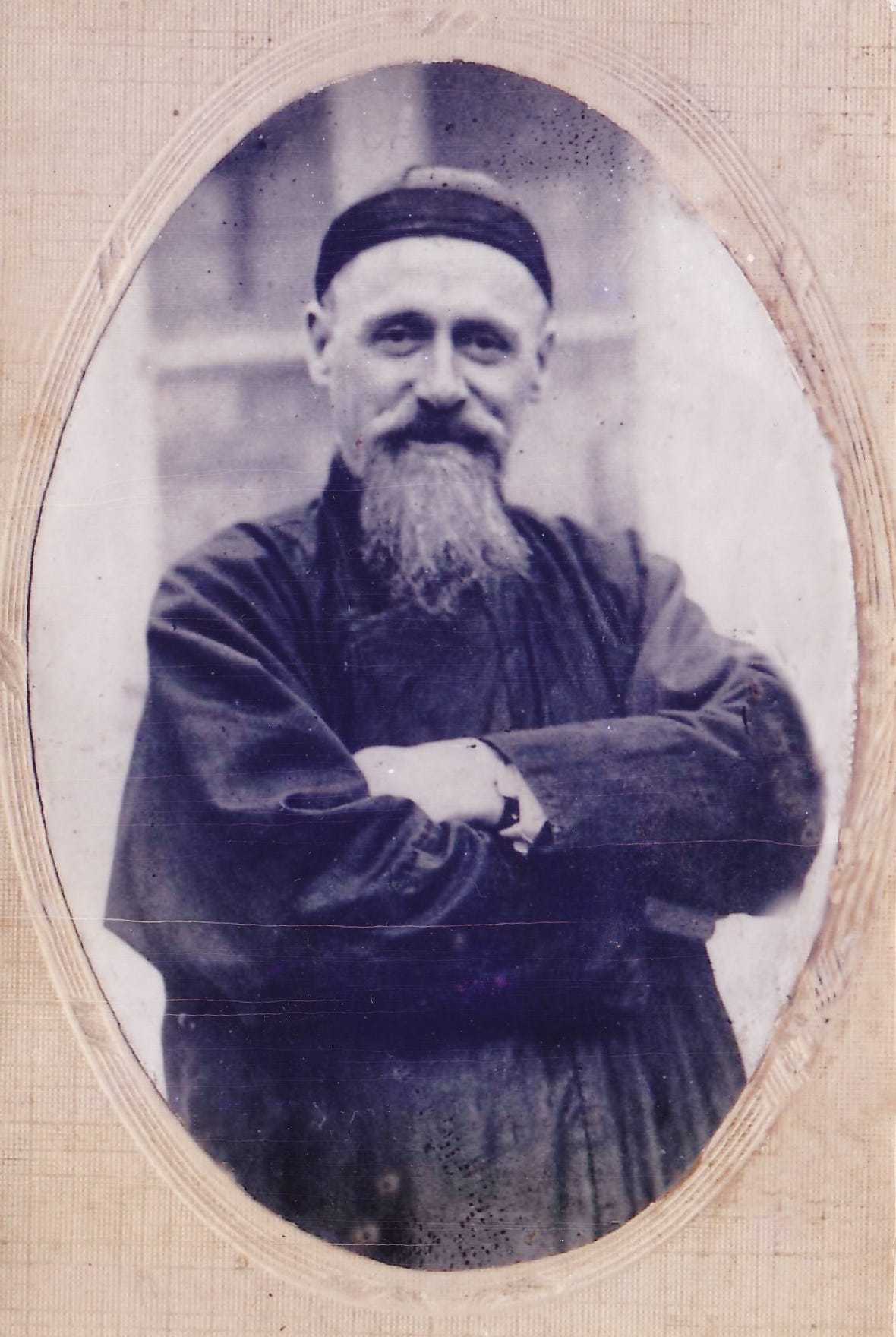

Ly Xia Foung, 1936.

Xia Foung furthered his ascendancy by making Blia Yao’s daughter, Lo Mai, his second wife in 1917. This was not a welcome development for Blia Yao as he had not given his approval to Xia Foung to kidnap his daughter; bridal kidnappings were only legitimated if the parents of the bride gave their tacit consent.14 The intergenerational nature of the marriage was also controversial as Xia Foung was a clan brother to Jer, Lo Mai’s stepmother, therefore, he was considered an “uncle” to Mai in the family tree.15 To avoid souring relations with the Ly clan, Blia Yao grudgingly allowed the wedding to go ahead.16 Lo Mai subsequently gave birth to Touby on August 13, 1919.17

Lo Blia Yao.

Touby was born into an ethnicity which was very unfamiliar with formal education. Most of the Hmong in Indochina lived as farmers in the highlands far away from educational facilities in the towns and cities. P. de Barthelemy, a commissioner in the town of Xiang Khouang, commented in 1898 that this lack of education among the Hmong and other highland ethnicities did not bode well with the administrative system that the French established in Laos:

“Laos is apparently organised for administrative purposes as though it was populated solely by [ethnic] Laotians. The laws are Laotian and so are the officials who apply them; and the Provincial Council, the embryo of our future Consultative Chamber, has never included a single representative of the mountain races. Fixed in the valleys from the beginning because of logic necessity, we have little by little centralised the indigenous administration in the hands of those who were nearest by… The oversimplification, on the contrary, increases our administrative difficulties because, to all those non-Buddhists who live in the mountains are still illiterate, orders can only be transmitted verbally; they are ill-understood and often ill-transmitted.”18

François Marie Savina, the Catholic missionary noted for his extensive ethnographical work on the Hmong, observed in April 1918 that there was a growing desire among the Hmong to have “chiefs of their own race and land that belonged to them.”19 He was also aware that the Hmong revolt that broke out that year had been caused by resentment towards indirect rulers, such as the Tais living on the Black River in Tonkin.20 Savina proposed that such tumult could be overcome by the creation of new provincial, district and sub-district positions for the Hmong.21

François Marie Savina, c. 1920s.

Mai Na M. Lee argues that these new positions were responsible for causing Xia Foung to fatally mistreat Lo Mai. She took a lethal opium dosage after he beat her for calling Touby a “gluttonous maggot” when he asked for a serving of cooked cow.22 An opportunity existed to stop Lo Mai from succumbing to the dosage, but neither her husband or his first wife showed interest in her.23 Lee states that Xia Foung’s indifference to Lo Mai’s condition was probably “the final revenge” on Blia Yao for his earlier effort in preventing him becoming a tasseng (sub-district leader).24 Blia Yao likely undertook this action as he begrudged Xia Foung for reporting to the French authorities that three tasseng leaders did not want him to become kaitong (paramount chief) of Xiang Khouang province.25 Therefore, Lo Mai’s remark was probably perceived by Xia Foung as an allusion to his “seemingly unquenchable thirst for power that led him to daily abuse Blia Yao’s name to visitors [to his house].”26 On the other hand, Nengher N. Vang disagrees with Lee that the feud had anything to do with Xia Foung’s behaviour.27 It was simply a case of a man unfairly treating his wife.

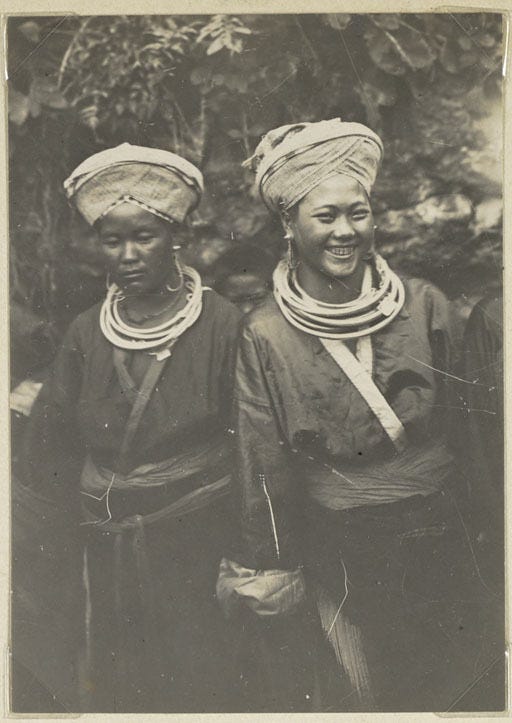

Lo Mai (woman smiling on the right) next to one of Blia Yao’s wives.

The division between the Lo and Ly clans was accentuated in 1925 when Blia Yao decided that his son, Tsong Tou, would replace him as tasseng.28 Xia Foung immediately resigned as his secretary as the French had attempted to nominate him for the same position, only to withdraw the proposal after Blia Yao made it clear that his son had to come first for such a consideration.29 Joua Kao, the Green Hmong leader of the Kue clan, took advantage of this schism by persuading Xia Foung to petition the French so that he could become a tasseng over the Green Hmong of Phak Boun.30 The French and Lao authorities accepted the petition, and Nong Het was divided into the Phak Boun and Keng Khoai sub-districts.31 Although Blia Yao managed to get the French authorities to imprison Xia Foung partly on the charge that he conspired to overthrow Joua Khao as tasseng, Xia Foung read that he was entitled to a hearing under French law.32 He was able to prove his innocence of the three charges33 brought against him and was accompanied home by the French officials who had imprisoned him.34

Xia Foung consolidated his trust with the French authorities by helping non-literate Hmong village chiefs with their paperwork and overseeing the continual maintenance of a major road.35 His efficiency as a bureaucrat stood in contrast to Blia Yao’s sons who were not prepared to assume their father’s responsibilities, as demonstrated with Tsong Tou, who’s chronic ill health made him an opium addict.36 Xia Foung’s paramountcy over Nong Het was completed when the French gave him the power to choose the next tasseng of Keng Khoai after Tsong Tou resigned over using his own money to pay for a tax shortfall.37 It was caused by the flight of the Laotian naikong (district leader) of Nong Het whom Tsong Tou had entrusted the annual tax with.38

The desire for his sons to be literate in order to survive caused Xia Foung to educate them from a young age.39 Touby’s first tutor was a Laotian named Thao Kham Pha who instructed him in French and Lao until ill-health forced him to quit.40 Touby was then sent to the primary school in Xiang Khouang and learnt Vietnamese through the Vietnamese teacher he and his brothers boarded with.41 After finishing primary school in 1934, Touby briefly studied at the Lycée Pavie before a bout of beriberi disease forced him to consider other options.42 He decided with his younger brother, Tougeu, to travel to Vinh in Annam to see if they could enrol in a school in Saigon or Hanoi.43 Instead, an opportune meeting with the French official formerly responsible for overseeing the annual examination at their primary school convinced them to enrol in the school in Vinh, as its diploma led to employment in the civil service.44 Touby acquired the diploma in 1939 and returned to Nong Het to help his father with administrative duties.45

In comparison, Blia Yao’s sons did not take education seriously. Fay Dang, the only child from his father’s second marriage, was remembered by one of his half-brother’s children as an excessive gambler who recuperated his losses by stealing and selling his father’s cattle.46 This did not serve Fay Dang well when it came to his ambition to become the next tasseng of Keng Khoai, as the French shared Xia Foung’s view that it needed to be given to a well-educated individual.47 Tsong Tou also impeded his half-brother’s ambition due to his support for Xia Foung after his resignation.48

Fay Dang was undeterred by these developments as he established a support base for his candidacy by travelling to Luang Prabang and giving a rhinoceros horn - an object Hmong leaders from Nong Het used to attain titles from the lowland authorities - to Prince Phetsarath, the viceroy of the town.49 Touby states that this father tried to be amenable to Phetsarath’s advocacy of Fay Dang:

“…Prince Phetsarath… wrote a letter to [Xia Foung]. He asked [Xia Foung] to assign Fay Dang a leadership position… [Xia Foung] asked Phiaxim Yaj Txoov Tuam to invite his brother-in-law [Fay Dang] to be the phutong [assistant to the district chief], aiding [Xia Foung] in administering the villages. Fay Dang did not agree. He sent a message back, saying that if his brother-in-law did not appoint him but insisted on nominating another individual from another clan to be the tasseng of Keng Khoai, then it was his choice. He just wanted his brother-in-law to know that someday down the line he would return to take over the tasseng position once held by his father.50

Xia Foung’s death from a horse-riding accident in October 1939 prompted the Hmong clan leaders of Nong Het to resolve the matter once and for all.51 Mao Song stated that they reached a consensus on appointing Touby as tasseng of Keng Khoai with Fay Dang’s consent as he was his nephew.52 This was done with gritted teeth, as Touby writes that Fay Dang was the only one who was unhappy with the situation.53 Although Alfred W. McCoy contends that Phetsarath got Xia Foung and the French authorities to promise Fay Dang that he would be appointed as the next tasseng,54 it is improbable that this occurred, as it would have signified that Fay Dang’s career progression was being delayed for no good reason.

The feud remained dormant for most of WWII as the Vichy government of Indochina (under Japanese control) relied upon Touby to continue his responsibilities as a tax collector and an enforcer of the French opium monopoly.55 This co-operation was thrown upon him by events outside his control given that Georges Catroux, the acting governor-general of Indochina (1939-40), had acceded to Japan’s demand in sending over a commission that ensured the Sino-Indochinese border was closed for Chinese arms traffickers facilitating the Sino-Japanese conflict.56 While this decision began the eventual process of Japan’s occupation of French Indochina, it needs to be noted that Catroux had unsuccessfully sought the assistance of the United States and the United Kingdom for military aid before he made his decision.57 He later defended himself in The New York Times in 1945: “We [the people of Indochina] would have had to face at once an attack by sea and attack by land. The result of the struggle, if joined, was therefore not in doubt. It was bound to lead us to the occupation of Indo-China by the right of conquest and as a result to destroy French sovereignty.”58 Touby would have similarly realised that it was safer for him to co-operate than resisting the Japanese and Vichy authorities.

The Free French attempted to take back Indochina by parachuting special commando teams into the Plain of Jars in Xiang Khouang province.59 These teams had been trained by British officials in insurgency techniques used to create ethnic armies.60 One of the parachutists was Captain L.H. Ayrolles, who met Touby and other Hmong leaders on March 6, 1945, to elicit their help for the clandestine operation.61 Second Lieutenant Maurice Gauthier writes that Touby “saw [this] collaboration as a means of obtaining more rights for his people.”62 The opportunity to attain legitimation from the lowland rulers along the Mekong also influenced Touby’s decision to help the French, as it would reinforce his paramountcy over Nong Het and end the threat posed by Fay Dang.63

This agreement could not have come at a more precipitous time in Indochina, as the Japanese launched an offensive against the Vichy authorities on March 9, 1945. This was caused by distrust over the loyalties of the Vichy officials due to Japanese defeats in South-East Asia and the conclusion of the Vichy regime in mainland France. Touby immediately found himself being asked by the French commander in Nong Het to hide supplies, weapons, ammunition and money; a task subsequently undertaken by Ly clansmen who took these items into the nearby mountains.64

Having witnessed Touby and the Ly clan assist the French in Nong Het, Fay Dang re-ignited the feud by reporting to the Japanese that his nephew was planning to rebel against them.65 Mao Song states that Fay Dang and his people tried to undermine Touby’s reputation among the Hmong by telling them that “[he] coveted the money and the things of the French so he killed the French in order to have those money and things.”66 Touby allayed Japanese suspicions by confessing that the French had forced him to hide the guns, ammunition and money, but he did not know where the French had escaped to.67 Following his release, Touby went into hiding with the French commandos.68

Touby’s flight caused the Japanese to appoint Fay Dang as the tasseng of Keng Khoai. However, the responsibility of reporting Touby’s whereabouts to the Japanese would harm Fay Dang’s relationship with other members of the Ly clan. When Touby’s wives and children had to be quickly reunited with him after their location had been revealed, Fay Dang sent Japanese soldiers to arrest them after delaying his decision for several days.69 Unfortunately, they had been hiding near the crop fields of their clansmen who lived in the village of Nong Khiaw, thus the soldiers proceeded to rape the females who worked in the fields.70

Mai Na M. Lee argues that Fay Dang’s delay may have resulted of “[finding] himself in the difficult position of not being able to say no to the Japanese who legitimated him.” 71 It is likely that he was aware of the prospective impact that the Japanese raid would have on his relationship with the Lys of Nong Khiaw, but he risked his own life if he did not say anything.72 This does not mean he was remorseful after the raid, as he subsequently extorted a substantial amount of money from them so that they could be be left alone.73 The ordeal made them permanently align with Touby.

In an attempt to switch Touby’s allegiance, the leaders of the Viet Minh in Nong Het - Lokhamthi Nakaya and General Le Thiep Hong - approached him to gain his support in taking over Indochina and permitting their agents to operate back and forth in the Plain of Jars.74 After meeting with them, Touby and Saykham, the new governor of Xiang Khouang province, decided not to work with them.75 The experience made Touby realise the strategic importance of uniting the Hmong behind him, so he sent Phya Anong, a former deputy governor, to ask Fay Dang to change sides.76 He refused to change his allegiance in the four times that Touby tried to negotiate with him, emphasising that he had been “wronged [perhaps by the near-fatal beating his brother (Nhia Vu) received from Ly men over the rape of their women] and refused to declare his loyalty to the French.”77

In response, Touby ordered his clansmen to attack Fay Dang’s village only to discover that he had relocated to Vietnam.78 The attack did not go without incident though, as two followers of Fay Dang died in the skirmish.79 Nhia Vu states that if these deaths and his own beating never occurred then his family and their followers would not have joined the communists.80 Nevertheless, Touby had clearly been willing to overlook what had happened between the Lo and Ly clans with his offer to Fay Dang. His refusal would only have made his nephew conclude that he was an enemy who had to be killed.

Fay Dang (second from left), Prince Souphanouvong (first from left) and Sithone Kommadam (first from right) in Vietnam’s Tuyên Quang province on August 18, 1950. This was photo was taken three days after the conclusion of the Congress of the Lao Resistance Front.

In early September 1945, French control over the town of Xiang Khouang was re-established by a Hmong militia led by Touby, with the rest of the province following suit four months later.81 France’s subsequent attempt to integrate the Hmong into the new Laotian state by making Touby the governor of an autonomous Xiang Khouang province was declined by him mainly due to the small amount of educated Hmong.82 His younger brother, Colonel Nao Kao Ly Foung, explained that Touby was aware that only eight of the Hmong were familiar with written Lao, but only three were really literate in it.83 Nengher N. Vang believes that such a refusal of sovereignty was wrong as it “dishonour[s] and desecrate[s] the sacrifice of all those who had fought, risked their lives, and died for the right of self-determination and national sovereignty in history.”84

However, being given such power is always dependent upon whether one is up to the task of exercising it. Touby knew that the Hmong’s lack of education and bureaucratic experience would jeopardise the governance of Xiang Khouang province, especially when one of their new tasks required looking after other ethnic minorities.85 Mai Na M. Lee also argues that Touby likely did not want to cause further disharmony to the Hmong in Laos by usurping Saykham’s position as governor.86 With these factors in play, it is understandable why Touby opted instead to be named chaomuang (paramount chief) of the Hmong while leaving Xiang Khouang’s administration to Saykham’s family.87

Touby’s militia which re-occupied the town of Xiang Khouang; most of them were Ly clansmen. Touby is to the right of his half-brother Toulia who stands on the far-left. The Frenchman in the photo was an officer named Jean Sakarek.

Touby gained importance as a military asset to the French Union forces during the First Indochina War (1946-54) as a result of his ability to requisition Hmong men.88 This was seen in their involvement in the Groupement de Commandos Mixtes Aéroportés (GCMA); a counter-insurgency group designed to establish French guerrilla activity behind enemy lines and develop a maquis among highland peoples, who, with Franco-American support, would harass the enemy and work in coordination with the French army to hinder enemy movements in the strategically important highlands.89 The GCMA’s finances depended on the illegal opium trade (outlawed in 1946) with the involvement of senior French officers.90 Touby’s experience as an opium enforcer also made him integral to this initiative as the French, in alliance with criminal syndicates in Saigon, relied upon him to convert opium into cash to pay the Hmong GCMA soldiers.91

While this initiative may seem hypocritical on the French’s behalf, the war necessitated quick revenues to be drawn up so that large numbers of soldiers could be paid. The French were not alone in using the opium trade, as the communists used it to survive until a new northern route on the Chinese border provided them access to both Communist China and large-scale communist bloc assistance.92 Christopher Goscha does not consider both sides involvement in the trade made them drug traffickers.93 Instead, he argues that opium enables cash-strapped states to run their wars cheaply, especially when it comes to paying for covert operations that governments do not want to pay themselves.94 Given that France was spending money to rebuilt itself after WWII, the Indochinese opium trade with its experienced operators, such as Touby, was a logical avenue for the French to finance their war effort.

Hmong loyalty to the French was shown in the dying days of the war. The precarious situation that the French Union forces found themselves in Điện Biên Phủ caused Colonel Jean Sassi, the leader of the GCMA’s “Malo” Group, to ask Touby whether he could find Hmong volunteers for a relief force called Operation D (D for Desperado). 95 This quickly manifested itself on April 28, 1954 with thousands of Hmong men reporting to the French on the Plain of Jars.96 Operation D began four days later with Sassi leading two thousand of these men to Điện Biên Phủ.97 Vang Geu, one of the Hmong commandos a part of the relief force, contends that “Vo Nguyen Giap [the communist military commander] knew one division was coming from Laos to rescue Điện Biên Phủ. That’s why he pushed so hard for victory before we arrived on the scene.”98 Operation D was only a few days away from arriving at the battle when the communist forces succeeded in overrunning Điện Biên Phủ on May 7.99

From left to right: Colonel Sang Rattanasamy, Major Vang Pao, Prince Saykham and Touby Lyfoung. They are inspecting Hmong volunteers for Operation D.

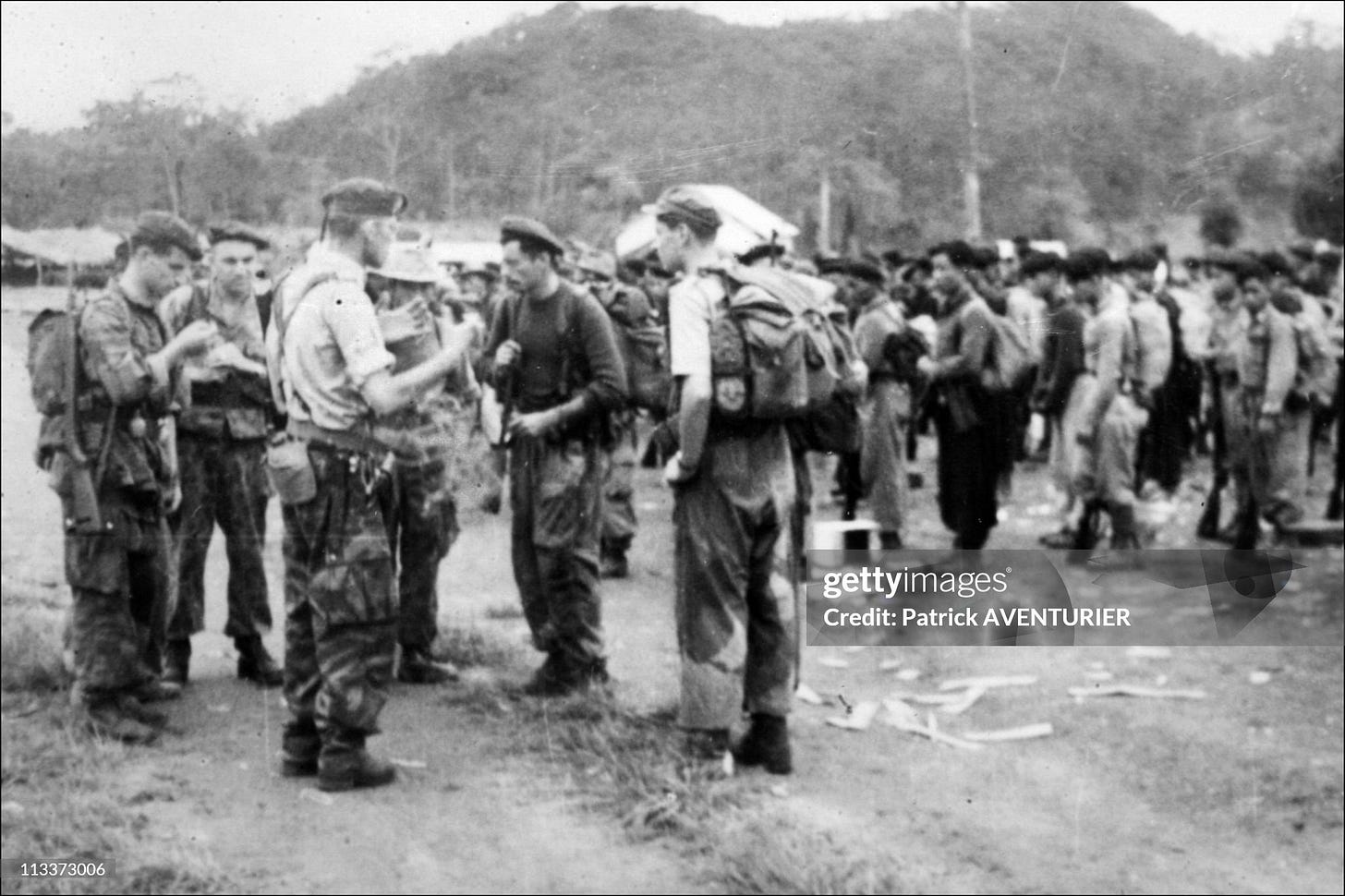

Jean Sassi (third from left in the white shirt) speaking to French officers as Hmong soldiers await them to launch Operation D.

A Hmong soldier dressed in French military fatigues.

Jean Sassi saluting the Hmong.

Operation D on the move.

The conclusion of the Geneva Conference in July 1954 precipitated the withdrawal of France from Indochina. With French personnel embarking off with feelings of resentment over failing to fulfil the promises they made to the Indochinese who aligned with them, the stage was set for the United States to enter the gap. Despite a brief show of unity towards a Laotian coalition government in the late 1950s, Touby and Fay Dang continued to fight for the Western and Eastern blocs respectively until the former was arrested by the Laotian communists in 1975. Touby was moved to the Vinh Xuyen re-education camp where fellow inmates reported that he was badly tortured and executed by a firing squad.100 His uncle continued in a governmental post until his death in 1986.101 Sadly, the wounds caused by such personal conflicts within the Hmong community of Indochina have never healed.

Mai Na M. Lee, Dreams of the Hmong Kingdom: The Quest for Legitimation in French Indochina, 1850-1960 (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2015), 68.

Ibid., 68.

Touxa Lyfoung, Tub Nips Lisfoom Tej Lus Tsey Cia [Words left by Touby Lyfoung] (Minneapolis, MN: Burgess Publishing, 1996), 14-15.

Alfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin, CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, Afghanistan, Southeast Asia, Central America, Colombia, 2nd ed. (Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books, 2003), 117.

Ibid., 116.

Ibid., 117.

Ibid., 116-117.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 194-195; McCoy, Politics of Heroin, 117.

After word spread to Vietnam and China that Nong Het was fertile and unoccupied, other Hmong clans migrated to the area.

Christopher Thao Vang, Hmong Refugees in the New World: Culture, Community and Opportunity (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2016), 219.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 169.

Ibid., 169, 199.

Ibid., 169.

McCoy, Politics of Heroin, 117.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 206.

Ibid., 209.

“5.5 Selected Biographies,” Unforgettable Laos, accessed January 10, 2024, http://www.unforgettable-laos.com/the-end-of-the-war/5-5-selected-biographies/

Pierre de Barthelemy, Le Laos, Plon, 1898, 139-140.

François Marie Savina, “Considérations sur la Révolte des Miao (1918–1921)”, L’Éveil économique de l'Indochine 373, 10.

Ibid., 10.

Ibid., 11.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 217.

Ibid., 217.

Ibid., 218.

Ibid., 214-216.

Ibid., 217.

Nengher N. Vang, “Review of Dreams of the Hmong Kingdom: The Quest for Legitimation in French Indochina, 1850-1960,” Hmong Studies Journal 16 (2015): 6.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 221.

Ibid., 221.

Ibid., 221.

Ibid., 221.

Ibid., 223.

The other two charges were that Xia Foung was involved in the Hmong revolt (1918-1921) as a strategist and had murdered a man who was a black magic practitioner.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 224.

Ibid., 225.

Ibid., 227.

Ibid., 238-239.

Ibid., 238.

Ibid., 230.

Ibid., 230.

Ibid., 230, 232.

Ibid., 234-235.

Ibid., 235.

Ibid., 235-236.

Ibid., 236.

Ibid., 233.

Ibid., 244.

Ibid., 239.

Ibid., 242.

Lyfoung, Tub Npis Lisfoom Tej Lus Tsey Cia, 48-49.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 249.

Ibid., 250.

Lyfoung, Tub Npis Lisfoom Tej Lus Tsey Cia, 146.

McCoy, Politics of Heroin, 118.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 254.

John E. Dreifort, “Japan’s Advance into Indochina, 1940: The French Response,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (Singapore) 13, no. 2 (1982): 279-281.

Ibid., 280-281.

“CATROUX DEFENDS INDO-CHINA REGIME: Without Aid of Allies or Vichy, He Says, He Tried to Save Colony by Stalling Radio Threats Cited Japanese Ultimatum Sent British Stand Similar Japanese Forces Superior Says He Yielded Nothing Catroux’s Account Supported,” The New York Times, August 2, 1945, 7.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 255.

Ibid., 255.

Ibid., 257.

Ibid., 257.

Ibid., 257.

Ibid., 258.

Ibid., 259.

Ibid., 259.

Ibid., 260.

Ibid., 261.

Ibid., 263.

Ibid., 264.

Ibid., 264.

Ibid., 264.

Ibid., 265.

Ibid., 270

Ibid., 270.

Ibid., 270.

Ibid., 270.

Ibid., 270-271.

Ibid., 271.

Ibid., 271.

Ibid., 273-274.

Ibid., 279.

Ibid., 279.

Vang, “Review of Dreams of the Hmong Kingdom,” 8.

Ibid., 279.

Ibid., 279-280.

Ibid., 279.

Ibid., 286.

“GROUPEMENT DE COMMANDOS MIXTES AÉROPORTÉS (GCMA),” On-Line Resource Site on the Indochina War at the Université du Québec à Montréal, accessed January 10, 2024, https://indochine.uqam.ca/en/historical-dictionary/554-groupement-de-commandos-mixtes-aeroportes-gcma.html

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 286.

Ibid., 286.

Christopher Goscha, The Road to Dien Bien Phu: A History of the First War for Vietnam (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022), 101.

Ibid., 101.

Ibid., 101.

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 293.

Ibid., 293.

Ibid., 293.

Ibid., 293.

Ibid., 293.

Unforgettable Laos, “5.5 Selected Biographies.”

Lee, Hmong Kingdom, 303.