The Kabyle Women of French Algeria: An Analysis into Legal Rights for Muslim Women

European imperialism saved the lives of Muslim women in Algeria.

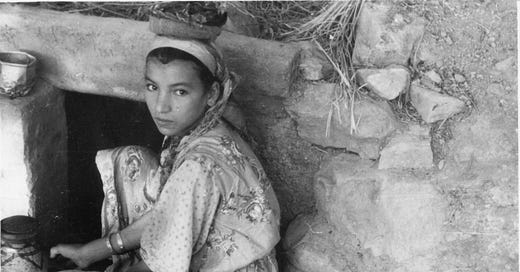

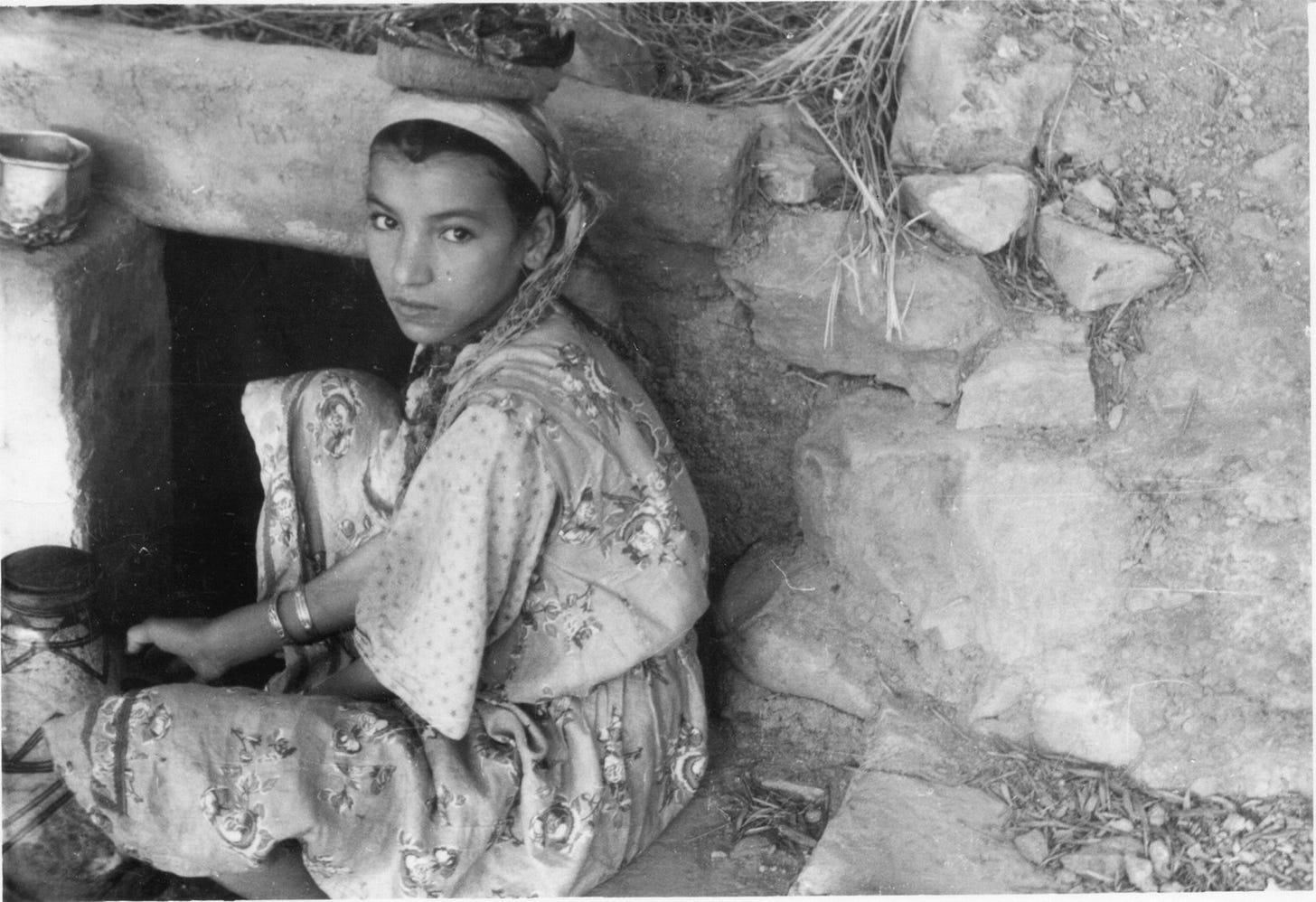

A Kabyle girl sitting next to a fountain, c. 1956.

When I visited Algeria, I met some very hospitable and charming women. Two of these women were Kabyle Berbers. Although the Kabyles speak French as their second language, I was able to converse with these women as they had been taught some English. Both of them told me that they were at different stages of their education: one was studying an undergraduate degree while the other was in high school. Their education gives them the opportunity to study and work in France or Quebec (if visa restrictions do not affect them). The older girl later told me that there was nothing for her in Algeria to make her stay. This sentiment is found among other ethnicities in Algeria, as a Chaoui Berber woman I met wants to follow in her sister’s footsteps and get a job overseas.

It is not surprising that they desire to finish their education in the West due to the better quality of life. I do not blame them, as Algeria leaves a lot to be desired: an economy that invests heavily in social aid for its population, single women living alone is not accepted, the absence of proper management for water utilities and rubbish collection, and a bleak landscape dominated by communist-like apartment blocks.

The opportunities that Algerian women seek overseas made me curious to see whether Kabyle women had similar opportunities during the French colonial period, as their ethnicity had the most interaction with the French in Algeria. There were instances of Kabyle women who lives were greatly restricted by their own families. However, the French attempted to improve their livelihoods by granting them legal protections in relation to marriage and inheritance, among other things.1

Rubbish piling up in the Algiers Casbah.

Passing apartment blocks.

Kabyle women did not have much personal choice in their own society during the French colonial period. Unlike today, where women can start relationships with men of their own choosing (this extends to foreigners), these decisions used to be made by fathers or other male relatives.2 This was economically advantageous for the fathers, as they could feed their families from the money they received from selling their daughters as brides.3 Given that these girls could be married before they reached puberty,4 their emotional wellbeing depended on how their husbands treated them.

In some cases, Kabyle men ensured that their wives could never have another romantic relationship. This was reflected in their ability to impose the thamaouok’t on their wives which prevented them from remarrying.5 While a man could choose to take another wife - as polygyny was permitted - a woman under thamaouok’t could only return to her parents home where, as described by Gloria Wysner, “[was] often unwanted and where [they could] be a heavy charge upon them.”6 In Laure Lefèvre’s 1939 thesis Recherches sur la condition de la femme kabyle, she mentions that a Kabyle woman was put under thamaouok’t at the age of fourteen or fifteen, remaining that way for the rest of her life, from 1871 to 1924.7

French magistrates in Kabylia had difficulty addressing such cases, as they were viewed as a last resort by the Kabyles. Georges-Henri Bousquet, a French jurist and Islamologist, observed that this was still the case by 1950:

“…when [French] judges are presented with a case, it is only when all other possibilities have failed: the intervention of parents, leading citizens. marabouts [Islamic religious leaders], and finally the djemaa [a Kabyle village council]; we cannot even say that French justice is considered a superior instance, but only as an instance that is equivalent to those that came before it.”8

The mountainous terrain of Kabylia minimised the amount of contact that Kabyle women had with the limited French presence in the region.9 Although the French introduced a decree in 1931 giving Kabyle women the right to divorce from their husbands on certain grounds - such as cruelty or deserting the marital home up to more than three years - some women found it too far to travel from their mountain villages to the courts, unless their parents were willing to help them obtain a divorce.10 For example, forty-five minutes were required for a one-kilometre walk between two villages separated by a ravine in an area where the French counter-insurgency expert, David Galula, served in during the Algerian War.11

A Kabyle village during the French colonial period.

Some Kabyle women attained legal protections on their own initiative. Fadhma Aït Mansour (1882/83-1967), the Kabyle poet and folksinger known for converting from Islam to Catholicism, highlights in her biography Histoire de Ma Vie that her mother, Aïni Aïth, subverted the custom for an illegitimately pregnant Kabyle woman to disappear in order to avoid familial shame by seeking out French magistrates.12 Fadhma was the child of a man who refused to admit paternity.13 This was problematic for her mother, as it caused the brothers of her deceased husband to coerce her into handing over her property and two sons.14

Instead of yielding to their demands, Aïni Aïth approached the local French magistrates to lay a charge against them.15 These magistrates took into account customary and Islamic law when devising just and humane solutions for disputes relating to personal circumstances.16 In Aïni Aïth’s case, the magistrates went against Kabyle customs: they appointed a guardian and deputy guardian for her children, made an inventory of her property, and decreed that she and her children must not be harmed.17 Another attempt to coerce Aïni Aïth failed due to French law, enabling her to keep her property and children for good. 18

Fadhma with her first child in 1900. No pictures exist of Fadhma as a child.

It is difficult to take seriously the oft-repeated claim that the French in Algeria were oppressors when they were actually protecting Muslim women from familial oppression. I do not believe it also serves Algeria’s current interests in educating young women while doing nothing to make them feel that they have a future in their own country. The Kabyle women I met are highly capable individuals who could change their country for the better. However, if they are lucky enough to obtain visas to study in France, there is no way that they will return to live in Algeria.

I was also going to focus on French education for Kabyle women but the topic is so expansive that it deserves up to three to four articles on it.

Gloria M. Wysner, The Kabyle People (Read Books Ltd., 2013), 66.

Ibid., 66.

Ibid., 66.

Ibid., 76-77.

Ibid., 77.

Laure Lefèvre, Recherches sur la condition de la femme kabyle (Algiers: Imprimeries “La Typo-Litho” et Jules Carbonel réunis, 1939), 73.

Georges-Henri Bousquet, Justice française et coutumes kabiles (Algiers: Imprimerie Nord-Africaine, 1950), 37.

Kabylia had very few European settlers. This caused the region to suffer from under administration. This was the same problem confronting the Aurès (another mountain range) prior to the beginning of the Algerian War in 1954. The scarcity of resources in Kabylia compared to the size of its population led one-third of Kabyle men to migrate to France for work, one-third to settle in Algiers or to work as seasonal labourers on the Mitidja Plain, and the rest to stay in the villages to care for the families: See the following source for more information: David Galula, Pacification in Algeria, 1956-1958 (Santa Monica, CR: RAND Corporation, 2006), 30.

Wysner, Kabyle, 75.

Galula, Pacification, 26.

Fadhma Aït Mansour, My Life Story: The Autobiography of a Berber Woman (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1989), 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5

Ibid., 5

Ibid., 5

Ibid., 5

Ibid., 9.